The Seagram Building – 375 Park Avenue, New York, NY

On my way to Rockefeller Center this past December, I decided to take a short detour over to Park Avenue. I wanted to see the Seagram Building. I’ve seen it before − walked by it many times and even hung out on the famous plaza, but I never gave it much thought − until recently. It has been described as one of the most beautiful buildings in New York City. The design has been copied so often since it was completed in 1958, that today it seems commonplace. However, architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s statement “God is in the details,” aptly describes this sleek and modern skyscraper. Only the finest materials were used − marble, bronze, travertine, and granite − and they were used with exquisite detail.

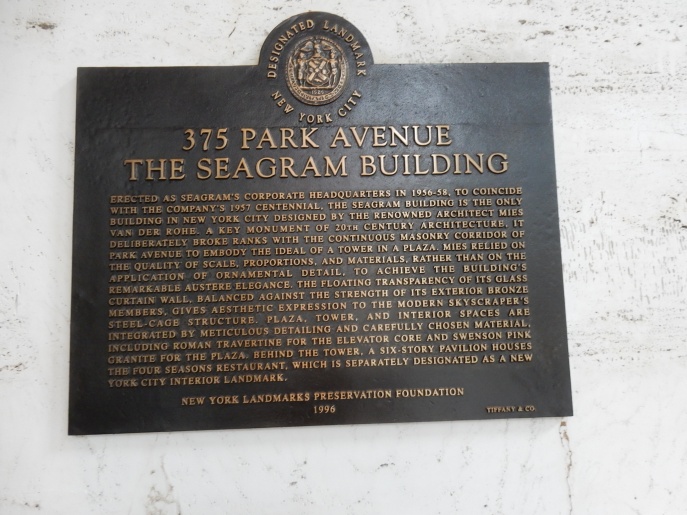

I hadn’t noticed the plaque on the front of the building before. Even if I had and taken the time to read it, I would not have connected anything it said to me. Until recently, the sentence on the plaque ending in “and Swenson pink granite for the Plaza” would not have held my attention. But after a trip to Maine last summer I have felt a personal connection to the Seagram Building and the granite spoken of here − the granite that makes up the beautiful plaza − the granite taken from the former Bald Hill Quarry in Wells, Maine where my Dad, Wally Paton, grew up and his father, George Paton, worked.

Plaque on the Seagram Building – “and Swenson Pink Granite for the Plaza”

“Bald Hill Quarry was owned by a conglomerate known as Swenson Pink Granite of Concord, New Hampshire. … Although the use of granite for steps or building foundations was common among the early settlers, the first granite quarry business wasn’t established until the late 1800’s in Concord, New Hampshire. … Under John Swenson’s leadership, the company continued to flourish and eventually added regional quarries like Bald Hill in Wells, Maine, where my grandfather worked. … eventually, Swenson would carry over 18 different colors, the pink stone coming from the quarries in Maine.” Excerpt from Journey Home: How a Simple Act of Kindness Led to the Creation of a Living Legacy by Bonnie Paton Moon

At the time of the Seagram Buildings completion, it was the most expensive skyscraper ever built. CEO of the Seagram Liquor Company, Samuel Bronfman, spared no expense in the construction of his company’s world headquarters. Over the years, it has received many awards. In 1960, the Plaza was declared “a source of inspiration” for its innovative, privately-owned public space, − “an open, urban plaza set back from the street creating the groundbreaking concept of pedestrian space.” The public plaza was a revolutionary idea and led to a landmark planning study called Social Life of Small Urban Spaces in which daily patterns of people socializing around the plaza were recorded.

In 1976 the exterior and in 1990 the interior, were designated New York City landmarks. In 1999, the New York Times declared it “the Millennium’s most important building” − important because Mies van der Rohe’s design ushered in a new era of skyscraper − one which showcased the building materials rather than covering them up with brick and mortar and ornamentation.

Not only were the original granite slabs making up the Plaza taken from Bald Hill, but when Aby Rosen, the new owner, embarked on a major renovation project in the year 2002, the 110 pink granite replacement slabs came from there as well.

“Perhaps the most remarkable rehabilitation project is underfoot. At a cost of $1 million, about 110 large granite paving slabs have been replaced. Close inspection reveals that the new and old stone looks identical – specks of salmon and gray, threaded with subtle veins of red and orange.

‘They are identical,’ said Sal Aiello of Concept National in Carlstadt, New Jersey, the contractor on the job.

“He knows because he tracked down the quarry himself, beginning with a dive into the book ‘Building Seagram.’ There, he learned that the original slabs were made of Swenson pink granite from Maine.” Excerpt from nytimes.com/2016/07/19 − What Stays as the Seagram Building Loses the Four Seasons.

I tracked down the Bald Hill Quarry myself this past summer, along with a few of the Paton family joining in the fun of connecting to my Dad’s childhood home. The house is gone, replaced by the Quarry’s office building, but much still looks like it did when my grandfather worked here during the Great Depression. The fields where my Dad roamed and the woods where he hunted as a child are untouched by development.

Millennium Granite (former Bald Hill Quarry) – 2018 (Photo by George Paton)

Discarded equipment and piles of stone now liter the land close to the Quarry, where wildflowers compete to reclaim their space. It is comforting to know that much is unchanged at the old Bald Hill (now thriving under the name Millennium Granite) making it easier to connect to my family history − a history that includes beautiful pink stone that traveled from Maine to New York, gracing one of the most beautiful buildings in that city.

Bonnie Paton Moon hanging out on the Seagram Building’s famous plaza – pink granite slabs from the former Bald Hill Quarry, Wells, Maine – 2018

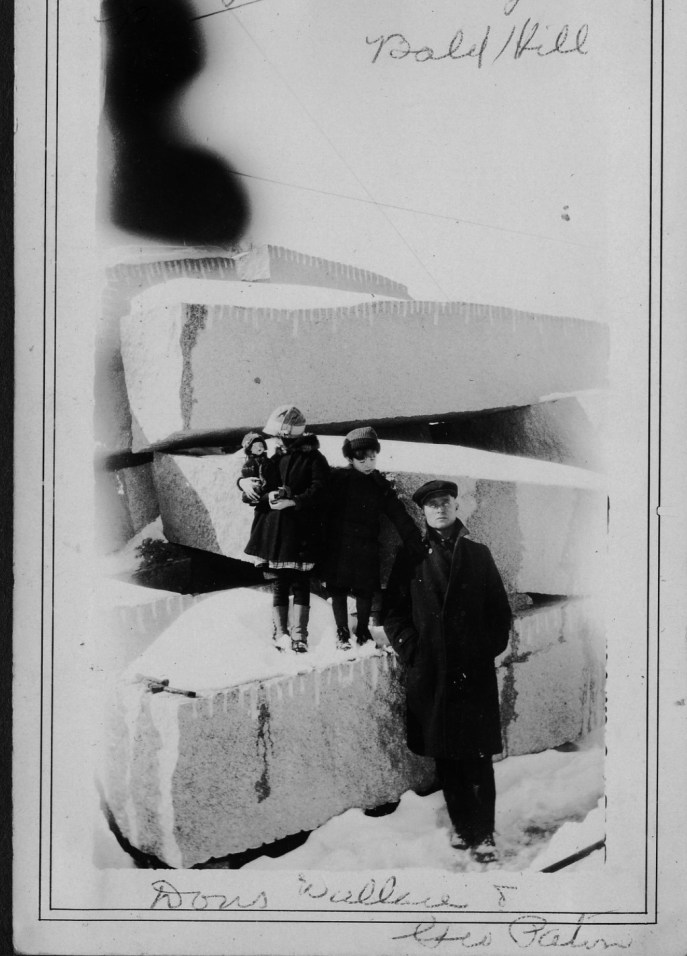

George Paton (back row center) at Bald Hill, Wells, Maine – 1939

My grandfather, George Paton with children, Doris and Wally Paton, posing on granite – 1929

Wally Paton’s childhood home – Bald Hill Quarry, Wells, Maine – 1934

What a great article about the Seagram Building and your family. It must be wonderful to be connected to such an impressive landmark. Thanks for sharing it.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike